County Magazine | January 29, 2024

Buffalo Soldiers helped build, defend today's Texas counties

The Buffalo Soldiers have a long history in Texas. The only all-Black regiments to serve in the U.S. Army, they were stationed after the Civil War in forts on the frontier from the Panhandle to the Rio Grande.

No one quite knows where the name Buffalo Soldiers came from. Some say the Comanches gave it to them because of their fierce fighting style. Other sources say it's because Native Americans thought the soldiers' curly hair resembled a bison's mane.

Today, the name carries great respect in the military and among Black soldiers nationally.

"Everybody had sweat equity in building Texas and the U.S., and those stories need to be shared and told."

— Richard Dolifka, Buffalo Soldiers Heritage & Outreach Program

When Congress reorganized the peacetime Army after the Civil War, in 1866, it authorized the creation of what would become two cavalry units and two infantry units of Black soldiers — the 9th and 10th and 24th and 25th, respectively — who helped defend against Native American raids as settlers pushed west onto the American frontier.

They served as armed security, patrolled forts and regularly engaged in combat with native tribes, such as the Apache, Kiowa, Cheyenne and Comanche.

But their impact also can be felt beyond the battlefield. The Buffalo Soldiers helped build roads, map water sources, lay telegraph lines and pioneer routes that eventually became Texas' highways.

"They basically settled the West," said Bexar County Commissioner Tommy Calvert, the first Black commissioner in Bexar County, where the Buffalo Soldiers were stationed in 1867 to help protect travelers and secure mail on the road from San Antonio to El Paso.

"Every post in the West had a Black regiment," said Thomas Smith, one of Texas' leading military historians.

Today, the legacy of the Buffalo Soldiers is preserved at military forts throughout Texas — at Fort Davis in Jeff Davis County, Fort Stockton in Pecos County and Fort Concho in Tom Green County, as well as in areas in Central Texas such as Bexar County and farther west into El Paso County at Fort Bliss.

In Tom Green County, Buffalo Soldiers made up half of the active-duty troops at Fort Concho during its 22-year active history, said Bob Bluthardt, the site manager at Fort Concho National Historic Landmark in San Angelo.

For the past 30 years, Fort Concho has held a Buffalo Soldier Heritage Day on the last Sunday of February, during Black History Month, with art, music and living history demonstrations.

Last year, with the help of the local chapter of the NAACP, a new Buffalo Soldier Memorial was erected in El Paseo de Santa Angela Park across from the fort, with 10 stone pillars that each tell a different aspect of the soldiers' history.

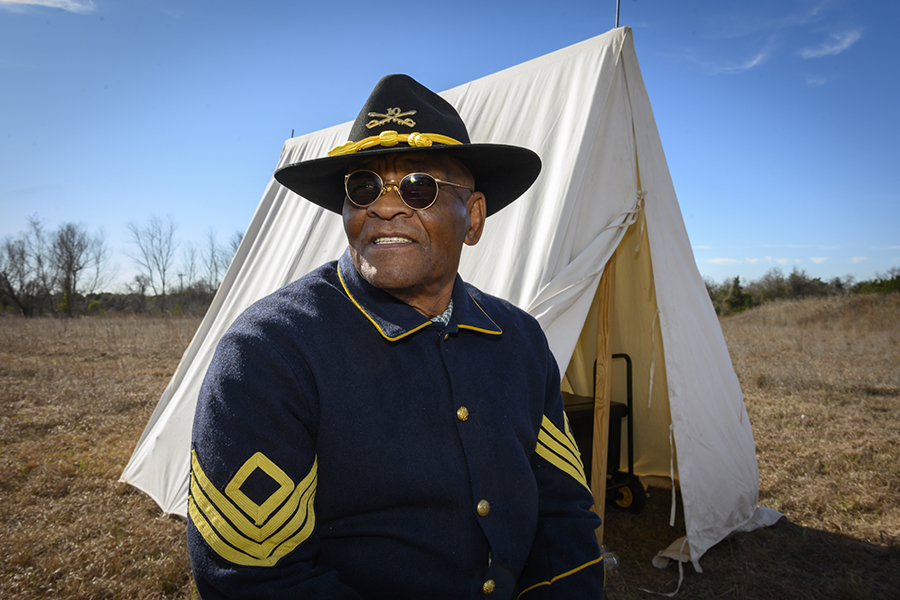

(Credit: Texas Parks and Wildlife Department and the Buffalo Soldier Heritage & Outreach Program)

"Their work — indeed, the work of all the men and women who staffed this fort and helped to create our current community — should be honored," Bluthardt said.

After the end of the American Indian Wars, the Buffalo Soldiers went on to fight in the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War and both world wars. In 1948, President Harry Truman signed an executive order ending racial segregation in the military. Today, men and women of all races serve in what is left of the historic Buffalo Soldier regiments.

Despite their important role in Texas, the U.S. and even abroad, Richard Dolifka of the Buffalo Soldiers Heritage & Outreach Program said their history and contributions often go unrecognized.

The outreach program, which is part of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, aims to change that by putting on living history programs at state parks so that visitors can learn about the everyday lives of the soldiers.

"It's a slice of life from back then, and you need to know where you've been in order for us to go forward as a society," Dolifka said. "Everybody had sweat equity in building Texas and the U.S., and those stories need to be shared and told."